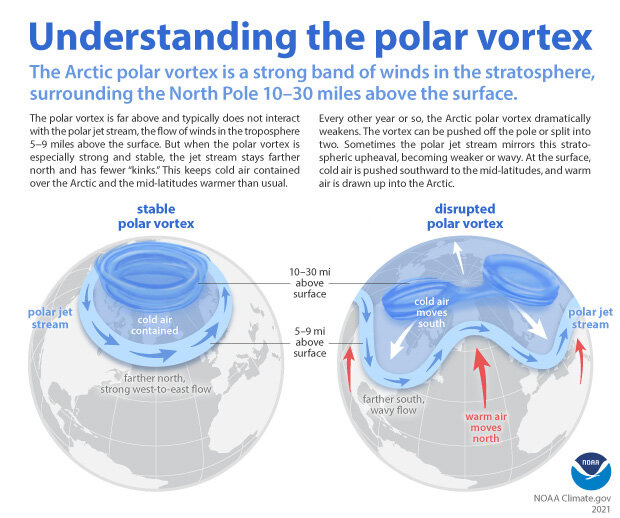

The term polar vortex is relatively new in the last couple of decades, but it is not a new phenomena. The occurrence of a polar vortex occurs about every other year when the circulation of the air at the Arctic pole becomes unstable. As illustrated in the graphic from NOAA, below, the cycle becomes weakened and dips cold air while pushing up warm air in a circle-turned-serpentine motion leading to the frigid temperatures in the otherwise temperate part of the Earth.

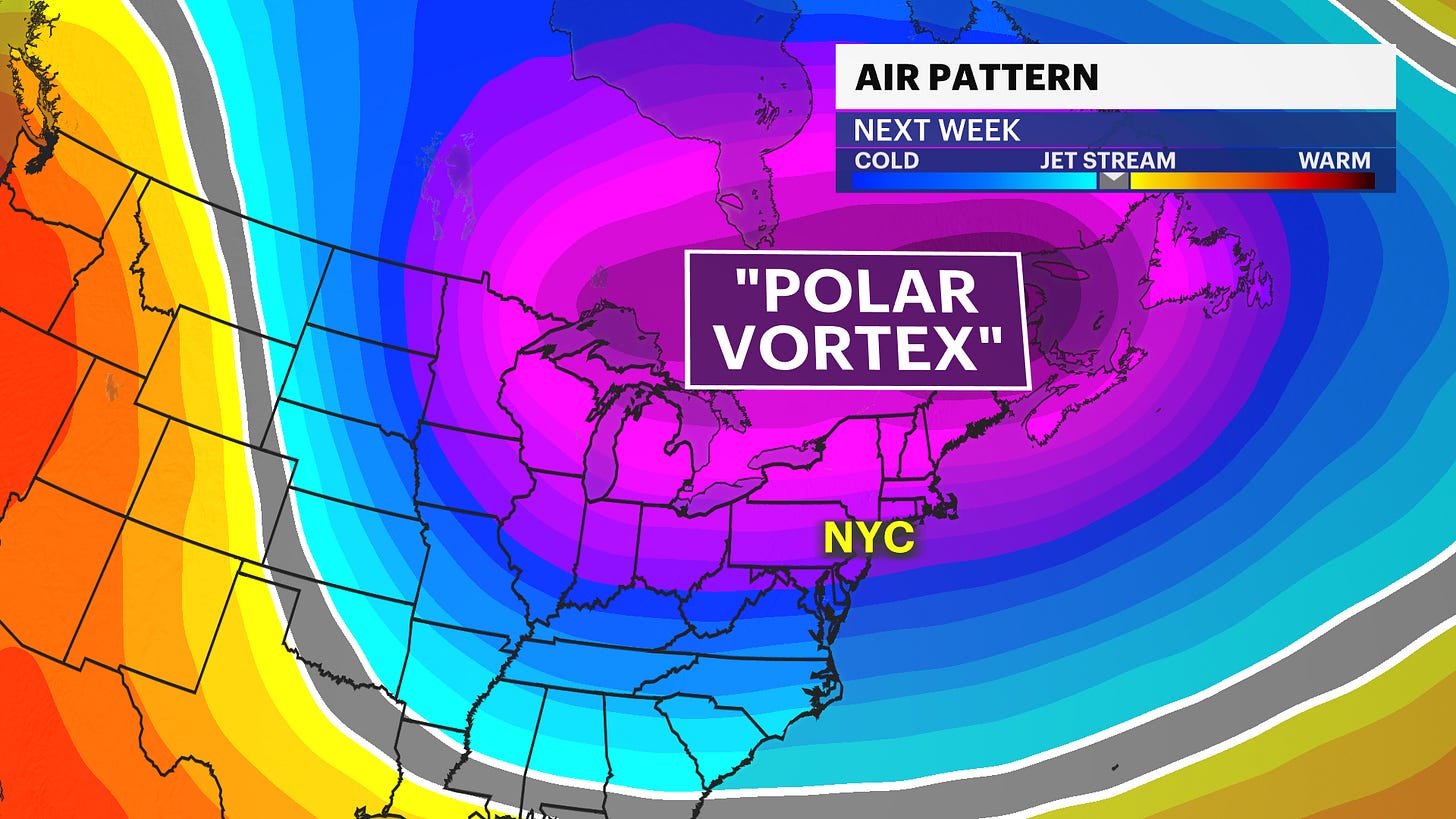

This has resulted in this pattern in the United States in 2025:

This can result in temperatures crashing significantly below normal cold weather by 20 degrees (F). This can persist for a couple of weeks and wreak havoc on unprepared infrastructure. But how does wildlife survive in these extremes?

What does wildlife do to withstand such grueling cold?

When food becomes scarce and high caloric needs occur together, we are familiar with the bears’ hibernation strategy. However, when a sudden drop in temperature occurs at any time and there has been no season of preparation by eating berries, there is another physiological state that some mammals can engage called, torpor.

Torpor vs. hibernation

Torpor can occur at anytime of the year, for short or prolonged periods in response to a sudden cold and requirement for increased caloric needs for body heat; compared to hibernation which is a winter process preceded by months of feeding in preparation for hibernation.1 (There are also two types of hibernation — facultative and obligate but not essential for this discussion). Further, torpor can look a lot like hypothermia, and it is the reduced body temperature in combination with a reduced metabolic rate that identifies the condition as torpor, rather than hypothermia.

Reptilian Brumation

The alligator has an amazing adaptation as one of the more cold-tolerant of the reptiles. It lives under frozen ice and can tolerate 40 degrees below zero. It has to poke its nose up through the ice to breathe but stays in this hibernation stage. Here is an alligator in North Carolina’s Shallotte River Swamp Park.2

Brumation in reptiles differs from hibernation in mammals in that alligators in brumation are in a state of suspended animation but have periods of activity and still continue to drink water to avoid dehydration, although they do not eat. Hibernation is a complete deep sleep with no activity.3

Then there is a bird’s regional heterothermy

Seeing ducks, geese and gulls standing on ice for long periods can be done because they are able to keep their core warm while their feet are almost frozen with a physiological process called regional heterothermy. This process allows the bird to conserve heat for the core, without expending energy to heat the feet. The heat exchange system is designed with veins surrounding arteries in the feet and the blood is warmed that is returned from the feet saving most of the warming for the core. The legs of birds are bone and tendons rather than the muscle and nerves which take more energy to heat. This begs a diagram so here is a graphic description of how this works (from Khan Academy):

What does adaptation mean for invasive species?

Whether an invasive species arrived in its new habitat on its own volition or was released or planted there by humans, it may not have the adaptations needed to survive the polar vortex weather. In Florida, during a dip to extreme cold, the spectacled caimans (an invasive crocodile species) disappeared completely after the freeze of 2010, unable to adapt to the cold; while native alligators survived.4

Native species that do not adapt well

The manatee is notoriously poor at adapting to cold weather and will succomb to death if the water drops to 68 degrees. Despite its appearance, it actually has little insulating fat to keep it warm. When it becomes cold, the physiological response seems to trigger a diminished immune system and it quickly becomes ill. This entire process is well documented and called the manatee cold stress syndrome.5

The opossum is another species that does not adapt well to the extremes of the polar vortex cold. While they can survive normal cold winters, their hairless tail and ears make them vulnerable to frostbite. After extreme cold periods like the polar vortex period, opossums may be seen without their tails or tattered looking ears from frostbite injuries.6

Animals in captivity

Most states and local governments have ordinances and laws to require shelter during extreme weather events. In Texas, care of a dog requires shelter and humane tethers during extreme weather defined as:

(4)A"Inclement weather" includes rain, hail, sleet, snow, high winds, extreme low temperatures, or extreme high temperatures. 7

Livestock care during extreme cold is regulated by states where it would be animal cruelty otherwise and there is no federal law regulating the care of cattle during the cold, but USDA does give advice.8 Calves are particularly at risk and frozen legs are a vulnerability and will almost certainly require euthanizing the animal if this happens. Providing shelter and lots of roughage (hay) is recommended to withstand cold weather. Most livestock owners want nothing more than to protect their livestock but that means they also have to be prepared for these extreme cold events. In Texas in 2016, 15,000 dairy cows froze to death in a snow storm,9 in the Texas Great Freeze of 2021, $228 million in livestock losses occurred.

Wildlife have developed adaptations for cold extremes whereas domesticated animals are displaced from their original habitats and unfortunately have to rely on humans to ensure their safety.

What does this mean for withstanding weather extremes for humans?

Looking ahead, researchers are considering how humans might benefit from these mammalian processes. Medical research has observed that the tissues of these mammals with the ability to go into a torpor state, unlike humans (homeotherms), can avoid potentially damaging organs during stroke or cardiac arrest. The potential to use torpor for space travel would allow for travel that might otherwise exceed human life spans.10

Final thoughts

The polar vortex reminds us that we are vulnerable to our environment, even as humans. It is also an opportunity to observe the incredible capabilities of wildlife to adapt to even the cold plunges of the polar vortex. That said, it is not without the casualties of the old, diseased, young and fragile individuals of the wildlife community that come with these extreme cold periods. In the Great Texas Freeze of 2021, fish on the coast were devastated by the cold and have taken years to recover. Texas Parks and Wildlife (TPWD) reported that 3.8 million fish among 60 species succombed to the cold along the Texas coast. Sea turtles were “cold stunned” and unable to navigate to warmer waters, requiring extensive rescue efforts to try to save them.11

Yet, remarkably, wildlife has developed physiological responses to extreme weather events that are unique to their animal classification and habitat. When an animal is domesticated humans are morally and sometimes legally responsible for protecting them from extreme cold. Physiological mechanisms for withstanding extreme weather events may even inform the future survival of humans if not on earth, in space travel or on otherwise uninhabitable planets.

Some thoughts for a cold, polar vortex’d day.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8764563/pdf/wellcomeopenres-6-19655.pdf

https://abcnews.go.com/US/alligators-north-carolina-poke-nose-ice-survive-freezing/story?id=52233678 (also photo credit for the alligator image).

https://scaquarium.org/brumation/

https://blog.nature.org/2018/01/04/how-extreme-winter-weather-affect-wildlife-polar-vortex/

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2003/08/030805071937.htm

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2003/08/030805071937.htm

https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/873/billtext/pdf/SB00005F.pdf

https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/news/blog/prepare-livestock-and-animals-ahead-severe-weather

https://www.chron.com/news/houston-texas/texas/article/20K-cattle-freeze-to-death-in-freak-Texas-blizzard-6738249.php

https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/ajpregu.00214.2014

https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/news/great-texas-freeze-february-2021