Mental illness - why can't we get better?

Science, policy and law have failed in our societal challenge of mental illness

The United States has not done a good job with mental health care.

The great concept of constitutional federalism works well for us, except when it doesn’t. Federalism is the process of governance in the U.S. where the federal government’s powers are limited to specifically named powers in the constitution and the states and people have any and all other powers (with a few exceptional circumstances). In the case of mental illness, there is no real federal policy because in our federalism model, mental health along with physical health falls to the states to decide how they would like to address it. States are historically underfunded when it comes to public healthcare, and fair even worse with mental health care.

It is estimated that one in five adults in the United States lives with a mental illness. That means that 20% of the adult population is struggling with conditions like depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. And yet, mental health care in the US is woefully inadequate. Just over half of adults with a mental illness receive any treatment at all, and less than 40% receive care that meets their needs.

This lack of care has real consequences. People with mental illness are more likely to experience homelessness, unemployment, and poverty. They are also more likely to be the victims of violence. And, perhaps most tragically, they are far more likely to die by suicide than the general population.

The criminal justice system is another area where the lack of mental health care in the US has had disastrous consequences. People with mental illness are much more likely to be involved in the criminal justice system, both as victims and as offenders.1 They are more likely to be incarcerated, and once they are in the system, they are less likely to get the treatment they need. As a result, they are more likely to reoffend and end up back in prison.

More and more people are beginning to talk about mental illness in a way that destigmatizes it and encourages people to seek help.

But there is a disincentive to seek mental healthcare in professions like law and medicine. Disclosure required for licensing could lead to suspension or ending ones career. Seeking mental healthcare in a divorce will almost certainly lead to deposing the healthcare professional and using any information gained in that process against that party in the adversarial setting.

In short, many people who need mental healthcare the most are the ones who have the greatest reason not to seek it.

This needs to change. We need to destigmatize mental illness and make it easier for people to get the care they need.

This problem has so many dimensions there is no one group of experts who can solve it. This is an issue that calls for interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary teams of experts and practitioners to work toward solutions.

So without claiming to have a solution, this article will try to lay out the reasons we should make this a high priority for our attention and support and the expected impact we should see with changes in the way we address mental illness and disability.

Recognizing degrees of mental illness

We do not recognize degrees of mental illness, rather it is particular types of mental illnesses without ranking in terms of severity with a few exceptions. Perhaps we should develop a different way of defining cases as a way to be more effective in addressing and treating people. Not just DSM definitions for particular illnesses, but more like a scale of severity. For example, destigmatizing mental illness so a law student can seek treatment without fear of jeopardizing their future admission to the bar is not the same as the mental illness that causes an ill person to commit a crime without fully understanding the consequences of their action. But we treat them all the same.

The kinds of mental illnesses that come from serving in active duty in the military should be recognizable and addressed, but even in that comparatively similarly-situated population, we have utterly failed to address the mental health treatment need.

Historical trauma has emerged as a potential theory for intergenerational mental health among populations with histories of genocide, slavery or other mass harms that cause harm from one generation to the next. Native Americans who have undergone generations of genocidal government policies suffer from historial trauma from one generation to the next.2 Recent scientific studies suggest epigenetics (the study of the effect of the environment on the action of genes)3 show that DNA is altered in mothers suffering from severe trauma during pregnancy.4

Meanwhile, anxiety and depression has increased by an unprecedented 25% worldwide, according to the World Health Organization in the recovery phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.5 Would this not call for a major research and treatment priority for the U.S. and the world? But there has been largely silence about addressing this problem.

The insanity standard in the law

Another area that tends to make binomial distinctions about mental illness, is law. The legal standard for whether a defendant is mentally ill or "insane" and can use that as a defense in a criminal matter, comes from case law almost two centuries old! Many states still use the M’Naghten Rule, from the 1843 case:

“ . . .at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong.”6

This is the test as to whether the defendant knew right from wrong and the consequences of his action; but there are at least three other tests that have grown from this one, that are not particularly better ones. It is called the “insanity” defense, and one is either “insane” or they are not.

Determining whether a person is mentally fit to stand trial is still either a “yes” or “no” diagnosis, because the legal process needs a timely answer with whatever information is available at the time.

The field of law has many shameful moments in its history of handling mental illness. The infamous case, Buck v. Bell (1927)7 was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court and the opinion written by one of the most esteemed justices in our nation’s history, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, making it all the more tragic. The court upheld the sterilization of Carrie Buck without her consent in order to ensure the nation would not be "swamped with incompetence . . . Three generations of imbeciles are enough."8 Later investigations decades later, showed that Carrie Buck was in school at the time and of average intelligence. She and her family were simply poor.9

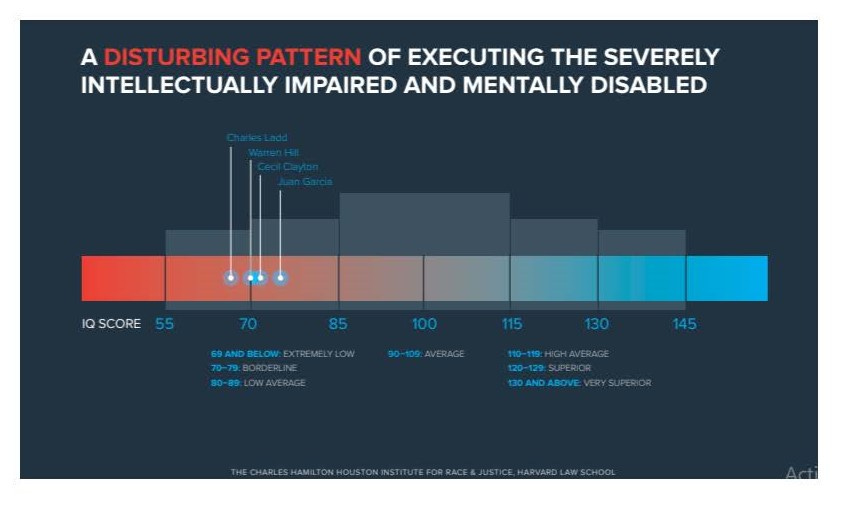

However, more recently, the courts have recognized in 200210 that criminals with mental illness should not be executed because it is a violation of the 8th Amendment which prohibits cruel and unusual punishment. Yet those who are executed are disproportionately mentally ill or disabled, according to a 2015 report which finds that of the 28 people executed in 2015, 68% suffered from "severe mental disabilities or experienced extreme childhood trauma and abuse" or other mental impairment (see graph below).11

Finding treatment for the mentally ill, early is clearly an indication from these statistics, and we could perhaps eliminate most of the crimes that come from this cause.

How did we reach this point of policy failure?

The ACLU has done a lot of important work to protect the mentally ill; however in the infamous case led by the ACLU to protect those who are homeless in New York City from government-supported treatment, based on the compelling government interest in protecting the public from homeless people who were dangerous.12 But did the homeless, many of whom are mentally ill, really have the capacity to make that choice? If they did not have the capacity should that decision be made by the state? Some would argue it should, others would find freedom to be mentally ill a choice of free will.

The last bill signed by Pres. Kennedy was legislation to dismantle the institutions that treated mental illness. The favored new treatment was community based and certainly more humane. Because Pres. Kennedy was assassinated before the second part of reform of the mental healthcare could be addressed at the community level, the result was turning patients out into the street without any care at all.13 So a well-intended policy resulted in the unintended consequence of having those with mental illness come into contact with the justice system with often a disastrous result.

How did we reach this point of treatment failure?

The treatments were isolating and ineffective in these institutions — from lithium to lobotaomies, the outcome was bleak for anyone who entered this places.

Then the biotechnology revolution led to new discoveries about how the brain worked, and maybe how we could increase the neurotransmitters that were causing mental illnesses like depression.

But just this year, new research has demonstrated that the drugs developed and used over the past few decades designed to correct a “chemical imbalance” in the brain, was simply a wrong theory. This new study showed that serotonin, thought to be responsible for reversing or preventing depression, actually does not have that effect.14 The research concludes that the "chemical imbalance" theory is still just hypothetical.

Where do we go from here?

All of this painful past has led governments to be reluctant to intervene in mental illness that leads to homelessness, drug addiction or crime. Instead, governments have engaged in programs like making needles safe for drug addicts, providing fentanyl test kits to make your street drugs safe, or prosecutors making unilateral decisions not to prosecute crimes that are otherwise still crimes.

Should we instead be looking at how to effectively treat mental illness and disability, rather than policy approaches that result in unintended consequences of making our collective selves worse off, rather than better? Treatment for mental illness could significantly impact crime, incarceration rates, executions, homelessness, lost quality of life due to depression, drug and alcohol use, unemployment and poverty. If we could impact all of these major social policy areas of our society, wouldn’t it make sense to have a major federal initiative to address it?

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537064/

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20190326-what-is-epigenetics

https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/disease/epigenetics.htm#

https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.677.7460&rep=rep1&type=pdf

https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-

prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide

House of Lords, 0 Cl. & F. 200, 8 Eng. Rep. 718 (1843). See https://www.quimbee.com/cases/m-naghten-s-case .

https://www.oyez.org/cases/1900-1940/274us200

https://www.oyez.org/cases/1900-1940/274us200

https://blog.petrieflom.law.harvard.edu/2020/10/14/why-buck-v-bell-still-matters/

Atkins v. Virginia (2002).

http://charleshamiltonhouston.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/2015-CHHIRJ-Death-Penalty-Report.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joyce_Patricia_Brown

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30339237/

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2022/jul/analysis-depression-probably-not-caused-chemical-imbalance-brain-new-study