Squanto teaching the Puritans how to plant and fertilize the crops. Image credit: Upfront Magazine

The first Thanksgiving in America was in 1621 if we are thinking about the idea of colonists and Native Americans sharing a feast. There was a fall harvest feast of deer, corn and shellfish shared between the Puritans who arrived on the Mayflower in 1620 and citizens of the Wampanoag Tribe. Many Puritans died of starvation during that first year, and had the Wampanoag not taught them to grow corn, and showed them where to hunt and fish they would likely have all starved. The reality is that the Wampanoag were not invited to the Thanksgiving feast of the Puritans with the food the Wampanoag had taught them to grow. They only joined the feast when the Wampanoag came to investigate why they were firing muskets.1

This tolerable relationship lasted only a generation, which ultimately deteriorated to ungrateful Puritan guests that overstayed their welcome, who then set out to commit genocide against the very people who had saved their lives.

But the Plymouth Colony was not the first settlement in America.

The Plymouth settlement was preceded by the Jamestown Colony in 1607, which held the title of the first settlement in America until recently. Many of these settlers starved to death, and Capt. Newport was sent back to England for more supplies. Chief Powhatan who led the powerful Powhatan Confederacy which occupied much of the Atlantic Coastal area, saw their plight and took pity on them, and sent gifts of food, without which the entire colony would have died. It would seem likely that the Jamestown Colony might have invited the Powhatan Indians to have a feast to share food, but they apparently never learned to grow food themselves. In fact, the relationship took a turn for the worse when in 1609 the Jamestown residents began demanding more and more food from the Powhatans during a drought year.2 By 1610, about 90% of the people had died of disease or starvation. Newly arriving settlers revived the colony business venture and learned to grow crops this time — tobacco. There appears that not only was there no evidence of a Thanksgiving, but there was also no sharing of the profits with the Powhatans who had introduced the tradition of smoking tobacco to John Rolfe and the other colonists and taught them to grow it.3

A discovery was made in North Carolina in the foothills of the Appalachians that is now identified as the first settlement in America, Ft. San Juan4 led by the Spanish explorer, Capt. Juan Pardo. Next to it was discovered the village of Joara from the explorers travel diaries. This relatively recent discovery in 2013, upended the longstanding distinction of Jamestown, Virginia as the first settlement in America. Now Jamestown is known as the first English settlement in America.5 It is still not widely known that the first settlement in America was, in fact, in North Carolina and not Virginia; and Spanish, not English.6

How likely was it that they had a Thanksgiving?

The Spanish conquistador, Capt. Juan Pardo (1566-1568), followed the earlier expedition of explorer Hernando de Soto into the interior of North Carolina (1539-1543). Capt. de Soto did not establish a settlement, but was primarily interested in finding a path to meet other Spanish explorers who were entering America through Mexico, all in the interest of looking for gold.7

This Spanish settlement, Ft. San Juan, included a number of buildings built in European style. But what helped identify it was the presence of a Catawba/Cheraw/Sara village that was identified in the explorers’ travel diaries. The village, Joara, had existed since at least the 1400s up until the 1700s.8

So is it possible that a Thanksgiving could have taken place at the first settlement, long before the Plymouth Colony Thanksgiving?

The expedition of Capt. Juan Pardo included about 30 men.9 From historical and archaeological evidence, Native women were hired or captured to cook meals for the Spanish explorers. Archaeological evidence has shown a well-used area for cooking. Before Plymouth Colony and Jamestown Colony, the Spanish Ft. San Juan residents needed food and were reliant on the Catawba/Cheraw/Sara to supply them with food and in this case, to also cook it!

At least one of the Spanish explorers brought with Capt. Juan Pardo married a Native woman, because she applied to Spain for his pension after his death.10 As Queen Isabella famously said, “cásense españoles con indias e indias con españoles” (“may Spaniards marry Indian women and may Indians marry with Spaniards”).11 But the relationship between the residents of Joara and the Spanish explorers of Ft. San Juan soured within 18 months, and at least half of the men were killed by the Catawba/Cheraw/Sara Indians of Joara.

Professor and archeologist David G. Moore, argues that the Spanish offended the Indians by possibly “demanding too much food or acting indiscriminately toward Native American women.” 12

From what we know about the Jamestown Colony demanding too much food, this seems like a likely explanation.

Would the Real Thanksgiving Please Stand Up?

The Thanksgiving we commemorate as a holiday on the fourth Thursday of November is one that recalls the first Thanksgiving as a day of joyous unity between Native Americans and Puritans from the Plymouth Colony in 1621. It is highly possible that other Thanksgiving events took place with the Jamestown Colony maybe 1608-09; or even at Ft. San Juan in 1586-87. What seems abundantly clear is that the colonists in all three of these earliest settlements would have starved to death without the help of the nearest American Indian Nations. What is also abundantly clear is that the colonists were all completely reliant on the Tribes who helped them, and in return the colonists demanded more and turned to genocide to take their food and their land.

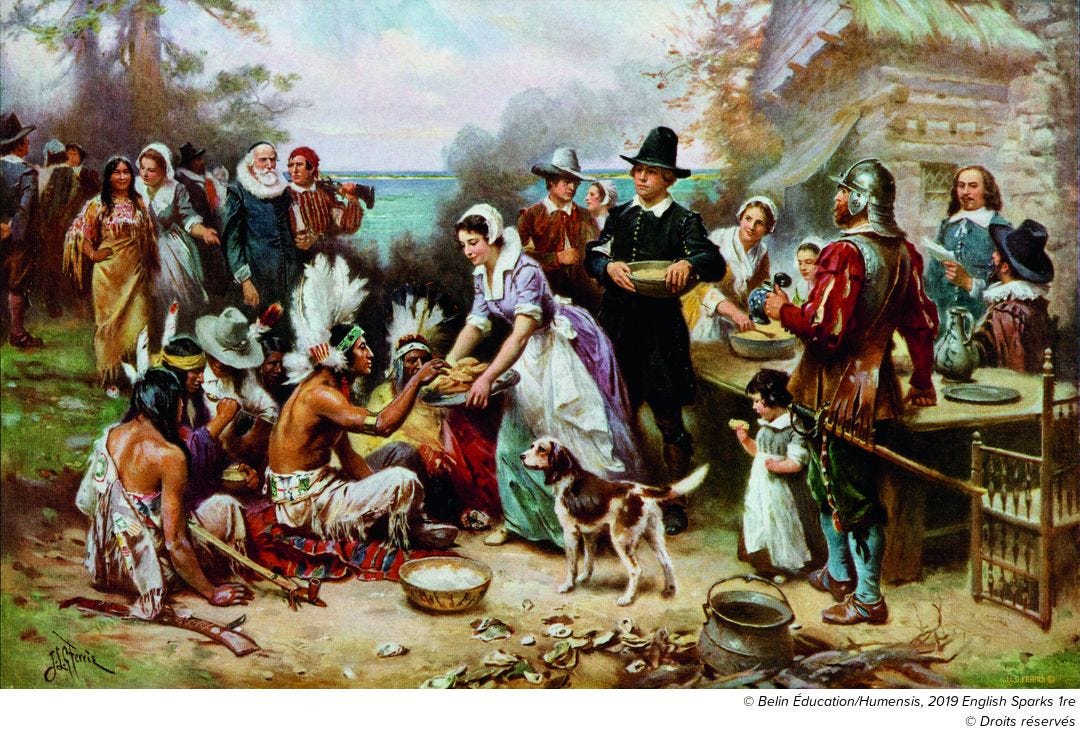

Looking at the most famous painting depicting the idealized idea of Thanksgiving by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, painted in 1912, ironically depicts the Native American guests as subordinate and the recipient of food being provided by the Puritans.13 No doubt, this famous image may be where some of the myth of Thanksgiving was conjured.

This idealized Thanksgiving that romanticizes the relationship of Native people with colonists, is more of one of recent invention at about the time of this painting. American Presidents have had varied views on the holiday since the first Thanksgiving was declared by President George Washington in 1789.14

What do the Wampanoag people have to say about Thanksgiving? Frank James, a member of the Aquinnah Wampanoag Tribe, called his Tribe’s “welcoming and befriending the Pilgrims in 1621 ‘perhaps our biggest mistake.’”15 He created a “National Day of Mourning” replacing Thanksgiving, that has become an annual event since 1970. 16

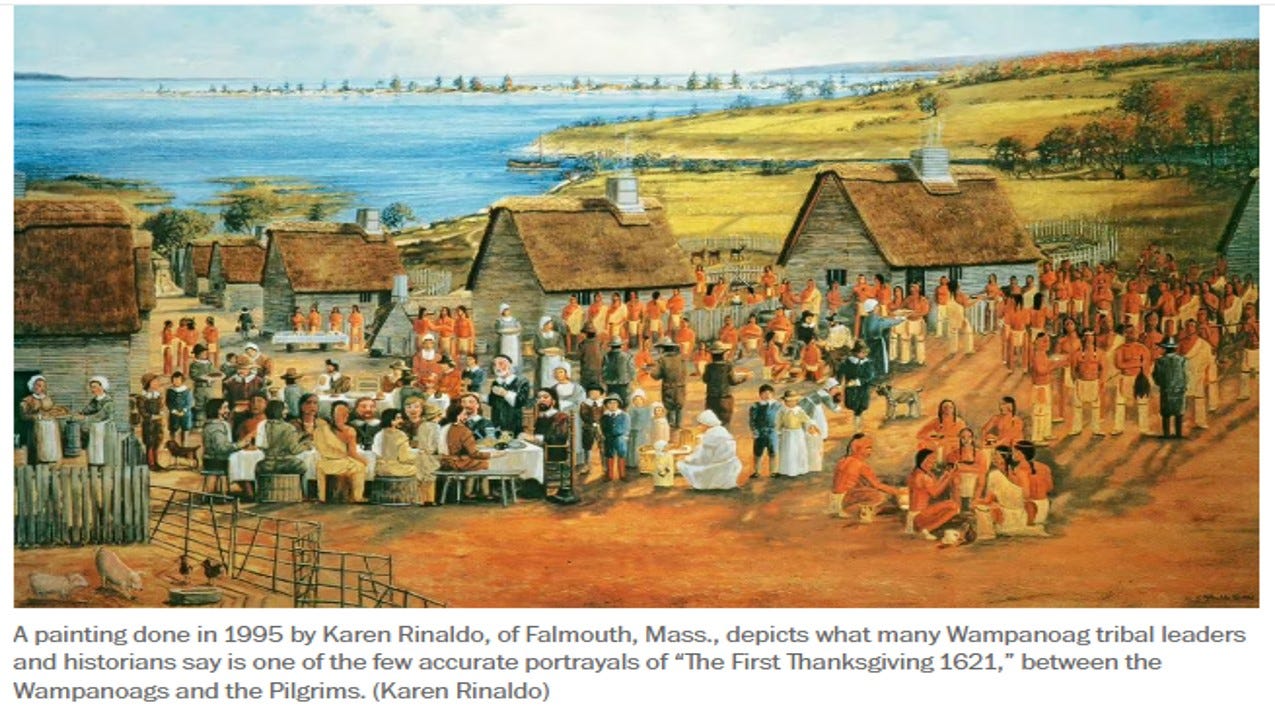

As far as depictions of the event, this 1995 painting by Karen Renaldo is considered to be a much more accurate portrayal of the Wampanoag and the Puritans at the first Thanksgiving in 1621.

Photo credit: The Washington Post

And so . . .

Thanksgiving has been a mix of myth and reality, depicting a harmonious feast between colonists and Native Americans. From the strained gatherings at Plymouth and Jamestown to the lesser-known interactions at Fort San Juan, the common thread is the indispensable aid provided by Native tribes to struggling colonists. Offered in goodwill, the favor was met with insatiable demands, exploitation and tragic killing.

The iconic Thanksgiving image, a product of historical romanticization, stands in stark contrast to the real events marked by dependency, betrayal, and genocide.

Yet, we can recognize this history and still use Thanksgiving as a time for gratitude and reflection, enriching its meaning by acknowledging the full spectrum of its origins.

Happy Thanksgiving.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2021/11/04/thanksgiving-anniversary-wampanoag-indians-pilgrims/ Compare this to the account in Kids National Geographic at https://kids.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/first-thanksgiving

https://www.nps.gov/jame/learn/historyculture/a-short-history-of-jamestown.htm

https://www.nps.gov/jame/learn/historyculture/a-short-history-of-jamestown.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_San_Juan_(Joara)

https://www.nps.gov/jame/learn/historyculture/a-short-history-of-jamestown.htm

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/23/science/fort-tells-of-spains-early-ambitions.html

https://wncmagazine.com/feature/search_gold

https://www.cambridgeblog.org/2013/08/finding-fort-san-juan-in-the-appalachians/

https://www.cambridgeblog.org/2013/08/finding-fort-san-juan-in-the-appalachians/

Melissa D. Birkhofer and Paul M. Worley, She Said That Saint Augustine is Worth Nothing Compared to Her Homeland: Teresa Martín and the Méndez Cancio Account of La Tama (1600) at https://nclr.ecu.edu/issues/nclr-2023/ (only available in print now).

Queen Isabella's Directive: In 1503, Queen Isabella I of Spain ordered her representative, Nicolás de Ovando, who was the governor of La Española (now the Dominican Republic and Haiti), to implement a policy that encouraged Spanish men to marry indigenous women and vice versa. This was seen as a way to integrate and establish better relations between the Spanish colonizers and the indigenous peoples of the Americas.

https://northcarolinahistory.org/encyclopedia/fort-san-juan/

https://www.llceranglais.fr/native-americans/the-first-thanksgiving-by-jean-leon-gerome-ferris

https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2021/11/a-presidential-history-of-thanksgiving/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2021/11/04/thanksgiving-anniversary-wampanoag-indians-pilgrims/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2021/11/04/thanksgiving-anniversary-wampanoag-indians-pilgrims/