Treaties and Tribes

When will we challenge the unconstitutionality of the 1871 Indian Appropriations Act?

The Treaty of Penn with the Indians. William Penn's 1682 treaty with the Lenape depicted in Penn's Treaty with the Indians, a 1771 portrait by Benjamin West

From the earliest days of colonization in the 1500s until 1871, leaders and the President of the United States were empowered to make treaties with Native Nations. They may have been one-sided but at least there was a respect for Native Nations as parties to a government to government treaty. Then the government to government relationship was changed forever with the Indian Appropriations Act of 1871 that removed the power of the President to make treaties with Indian Tribes. The U.S. Constitution, however, gives the President that power:

Art. VI, Clause 2. He shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur; 1

With the passage of the 1871 Act, Congress declared that "no Indian nation or tribe within the United States would be recognized as an independent nation with which the United States may contract by treaty."

This statute should have been challenged and found unconstitutional as a violation of the separation of powers doctrine.2 The separation of powers doctrine ensures a checks and balances system where each of the three branches of government have particular duties outlined in Arts. I, II and III of the U.S. Constitution.

If you are analyzing this clause using an originalist analysis, making treaties with Indian Tribes was a priority for the Department of War in order to settle wars and conflicts over land and expansion under the “Manifest Destiny” doctrine. When the drafters of the Constitution wrote that they were undoubtedly acquainted with this major undertaking with the U.S. Indian Tribes. In fact, the process outlined in Art. VI, Clause 2 of the Constitution was followed, having Indian treaties ratified by Congress.

The first U.S. Supreme Court, with Chief Justice John Marshall confirmed this clause applies to treaties with Indians, holding that

“The Constitution, by declaring treaties already made, as well as those to be made, to be the supreme law of the land, had adopted and sanctioned the previous treaties with the Indian nations, and consequently admits their rank among those powers who are capable of making treaties. The words ‘treaty’ and ‘nation’ are words of our own language, selected in our diplomatic and legislative proceedings, by ourselves, having each a definite and well understood meaning. We have applied them to Indians, as we have applied them to the other nations of the earth. They are applied to all in the same sense.”3

The constitutional Presidential power to make treaties with the Indian tribes was demonstrated to be coextensive with the power to make treaties with foreign nations, in cases in 1872, 1876 and 1908.4 So it is clear that the treaty clause applies to Indian Nations.

Yet, in 1871, in an otherwise routine Indian Appropriations Act, the U.S. Congress put an end to the President’s power to make treaties with Indian Nations. The Act further said that Indian Tribes were no longer “independent nations” so they were no longer to have treaties.

Colorado Encyclopedia5

Why 1871?

The United States had categorized Indian Tribes by placing Indian Affairs in the U.S. Department of War, up until the establishment of the U.S. Department of Interior in 1849.6 This signaled a shift in Indian Policy to one where the U.S. would act as trustee rather than as enemy or conqueror. But the official declaration for the end of war with Native Nations happened in 1871.

Treaties were seen as bargaining chips to end war with Tribes and in exchange for an end to attacks and raids, Native Nations were given hunting and fishing rights and a place to live with boundaries to exclude others — reservation lands. With the end of war, the end of treaty making was the logical next step in the mind of legislators. Yet, it was an Art. II power, not an Art. I power.

The costs of Indian Wars and Treaties were both high, and Congress wanted to do away with it. They attempted to that with the 1871 Act. However, the wars did not stop. In 1881, the U.S. Army was debating whether they could execute three Apache Scouts who were part of the U.S. Army for mutiny without permission of the President. If they were still at war, they did not have to get the President’s permission, but if there was a declaration of the end of war with Tribes, then they had to get the President’s permission. They ended up asking permission and it was granted.7 As late as 1890, the Massacre of Wounded Knee was the result of the U.S. Army shooting and killing as many as 150 children and elderly Sioux in a pointless massacre out of fear of a brewing discontent among the Sioux. The resistance by the Plains Indian Tribes raged through the end of the 19th Century. In 1911 a massacre of four Cheyenne people by ranchers occurred in Nevada. And in January 1918, at Bear Valley, in southern Arizona, The Battle of Bear Valley was fought.

So who would challenge the constitutionality of this statute?

The end of treatymaking did not affect Indian Tribes with treaties. It only affected Tribes without treaties, and in 1871, that could mean Native Nations in most of California, Arizona and all points west. These Native Nations likely did not plan on treaties, typically seen as a cease fire agreement. They likely planned on living free and independent as they always had, unaware of the certainty of the flow of Manifest Destiny that would soon claim all of their homelands. Only Indian Tribes in the process of negotiating a treaty would have seen an end to treatymaking and had a controversy. Perhaps they would have been happy to end the negotiations and it appears there are no examples of this happening. A “case or controversy”8 is required by the constitution to enter the judicial system of resolution.

The Executive Branch is the party having its Art. II powers being reduced and so should be the party to challenge this Legislative Branch action that is a violation of the Separation of Powers doctrine. But it is the Judicial Branch that should resolve that Constitutional question and it is very likely the Judicial Branch may determine this to be a “political question” and not accept the case. Even if the Executive Branch was in favor of ending treat making power with the Tribes, allowing this action to diminish Art II powers was a failure on the part of the President.

How would Native Nations without Treaties be Recognized in this Government to Government Relationship?

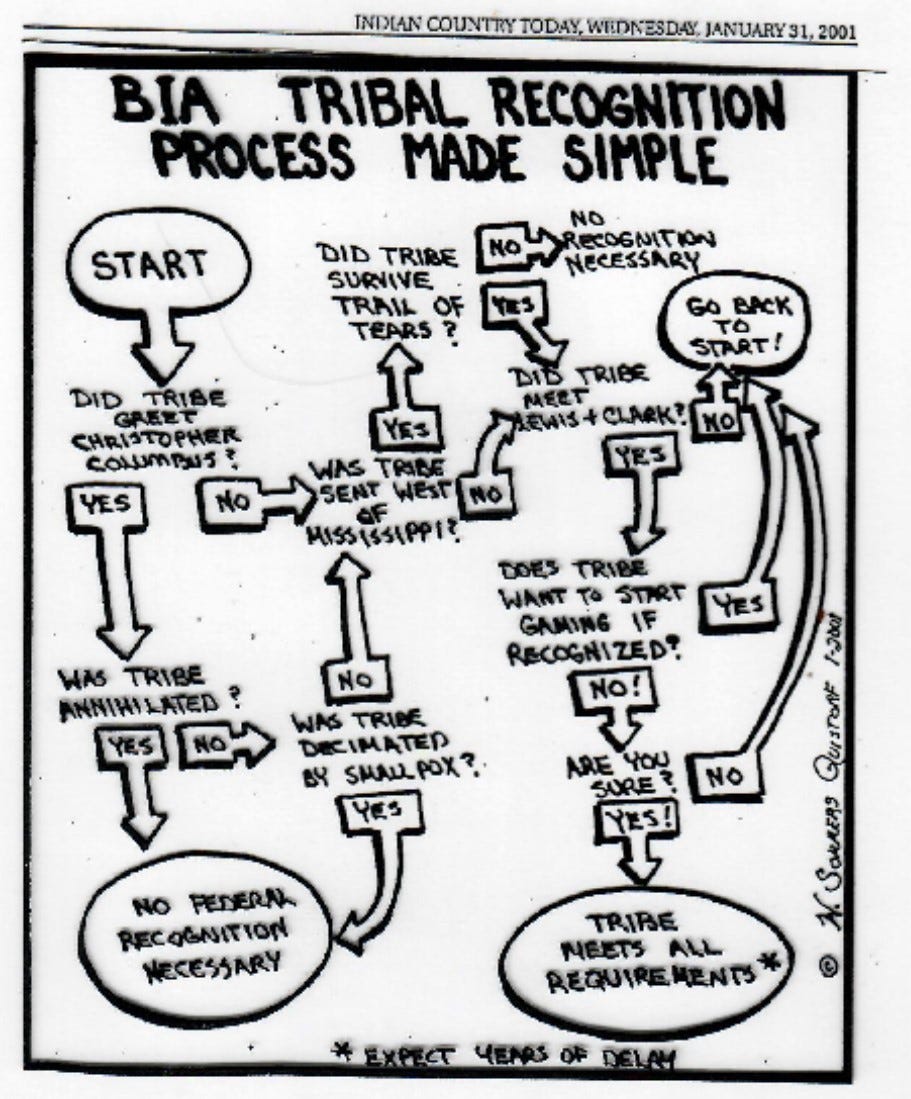

The Executive Branch and sometimes the Legislative Branch took up the job of recognizing Indian Tribes. The Legislative Branch is empowered to pass legislation recognizing a particular Native Nation. But in the 1980s. the Bureau of Indian Affairs were given the administrative task of creating criteria to use to determine if a Native Nation met that criteria for recognition. They made some absurd requirements. One is whether you still have your language (regardless of the fact that the federal government had a well-funded program to beat any young children in residential schools caught using their Native language). Whether you had been in continuous existence (regardless of the fact that smallpox epidemics brought by colonists often wiped out entire villages that reunited other other Tribes to survive.) .

My favorite way to sum up the criteria developed by BIA is in this political cartoon. It illustrates how the criteria is biased against granting recognition:

So in answer to the question, when will we ever challenge the unconstitutionality of the 1871 Indian Appropriations Act? Without a case or controversy — probably never.

U.S. Const., Art. VI, Cl. 2

https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/separation_of_powers_0

Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. (6 Pet.) 558 (1832).

Holden v. Joy, 84 U.S. (17 Wall.) 211, 242 (1872); United States v. Forty-Three Gallons of Whiskey, 93 U.S. 188, 192 (1876); Dick v. United States, 208 U.S. 340, 355–56 (1908).

https://www.doi.gov/about/history

https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2009/summer/indian.html

U.S. Const., Art. III, Sec. 2, Cl. 1