Once the Food and Drug Administration determined that bioengineered foods were not substantially different from the original food plant, that meant no labeling was needed to warn or notify the consumer. Statutorily, labels are for health and safety reasons and since bioengineered foods posed no health or safety threat— no language could be required on labels.

But what if states with bioengineered-conscious citizens wanted labeling? The state of Vermont did just that and they made a law requiring labels to disclose milk with an added hormone, rBST (recombinant bovine growth hormone), that is administered to cows to increase milk production. But since FDA had also found this milk was the same as any milk, no label was required — in fact, Vermont could not make producers add that information to its label. The U.S. Federal District Court, Vermont District, opined that it was a constitutional “right not to speak” decided in International Dairy Foods in 1995.1

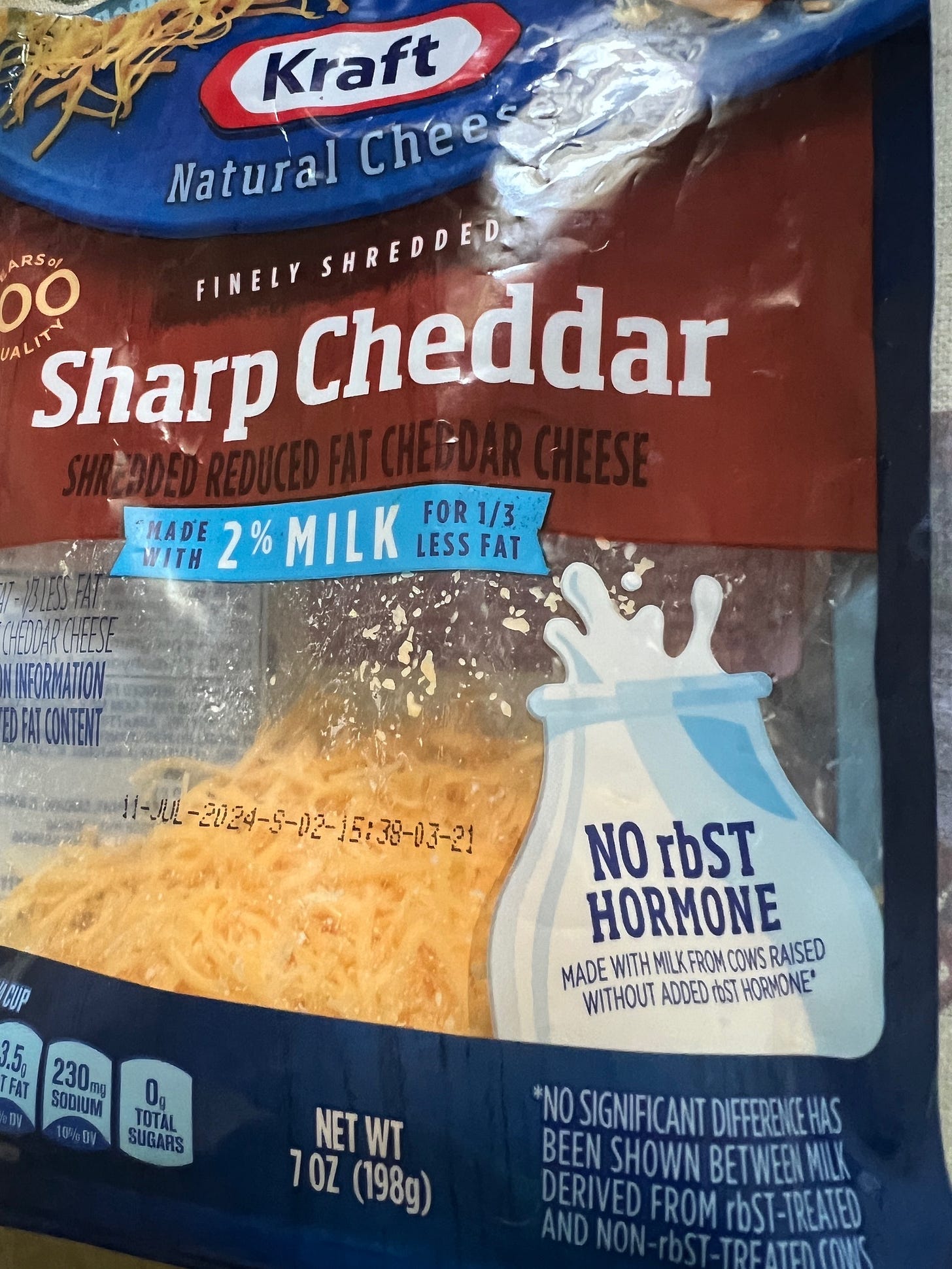

But consumers were not satisfied with this answer, and many voluntary labeling organizations were born, to add on a volunteer basis. This new labeling information created a whole new market for non-bioengineered products with these labels — “rBST free”, for example.

Consumers also continued to petition FDA to label bioengineering foods, citing simply the need to know. But that was not a basis for which FDA had authority to require labels. Eventually, Congress took action.

National Bioengineered Foods Disclosure Act of 2016

In 2016, the National Bioengineered Foods Disclosure Act preempted all other state laws, that may have been used for labeling bioengineered foods. This new authority for FDA allowed labeling not for health and safety reasons but for information purposes.

This was an amendment to the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946, which required the USDA to promulgate regulations to label food containing genetically modified organisms (GMOs). In order to overcome a Constitutional right not to speak articulated in International Diary Foods, a Congressional finding that included a compelling government interest that outweighed the right-not-to-speak was required. Congress has Commerce Clause authority to regulate this area, because of the different labeling programs from state to state, could be a burden on interstate commerce.

In 2017, USDA promulgated regulations for labeling bioengineered foods. These regulations make food manufacturers, importers and retailers who package and label food for retail sale or bulk sale subject to this labeling requirement. Excluded from the scope of this regulation are restaurants and small food manufacturers (defined as having annual receipts less than $2.5 million). Lists of bioengineered foods and their trade names will be used for uniformity and disclosure on labeling. Actual knowledge that the seller has a bioengineered food not on the list, comes with an obligation to disclose it.

Detectability is one standard for disclosure. Exemptions for up to five percent that is inadvertent or technically unavoidable the regulated entity must use standard processes. However, if there is an intentional use of bioengineered substance or ingredient a disclosure is required. However, an animal that is fed a bioengineered food, does not require disclosure. Any foods certified under the National Organic Program (NOP), does not require disclosure.

Disclosures must be made on the display panels at the point of sale so that a consumer can see it. Four options for disclosure include on-package text, symbol, electronic or digital disclosure or text message (information on the package that will send an immediate response to a consumer’s mobile device). The text should say “bioengineered food” or “contains bioengineered food ingredients”. A specific symbol must be used, if the symbol option is selected.

December 21, 2018, the USDA released a final rule with the authority of the National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Act of 2016, regarding the establishment of new national mandatory bioengineered (BE) food disclosure standard (NBFDS or Standard). The rule announces,

“The new Standard requires food manufacturers, importers, and other entities that label foods for retail sale to disclose information about BE food and BE food ingredients. This rule is intended to provide a mandatory uniform national standard for disclosure of information to consumers about the BE status of foods. Establishment and implementation of the new Standard is required by an amendment to the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946.” 2

The statute continues to update the lists of bioengineered foods that must be disclosed, and that list is certain to grow.

In 2019, the Natural Grocers challenged the regulations in a law suit against USDA for failure to comply with the Administrative Procedure Act, as well as claiming the regulation is beyond the scope of the statute. In the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California (Natural Grocers, et al. v. Sonny Perdue, Secretary of USDA, et al., No. 3:20-cv-05151) they make four claims: (1) the use of QR codes was arbitrary and capricious and contrary to the NBFDS Act; (2) the USDA’s exclusion of the terms “GE” and “GMO” is arbitrary and capricious and confusing to consumers; (3) the exclusion of highly refined foods was arbitrary and capricious and beyond the scope of the NBFDS Act; and (4) the Free Speech right of industry to label foods produced through “genetic engineering” is a violation of the First Amendment.

So you may want to see how this looks on labels on your food. Looking at the labels in your pantry or cabinet shelves or on your next visit to a grocery store may be surprising. It also may be surprisingly confusing, and that is part of the problem with the possible ways that a product can be labeled. In my course on Agricultural Biotechnology Law this spring, one of my students told me this became a family conversation, so I thought it might have some broad interest here.

So here is an example. Take a look at this Hamburger Helper box label, above. On the far right of the photo, you will see the last text on the label addresses the bioengineering content. Is this label in compliance? (Pick the best choice below.)

A. Yes, it complies because it discloses the information about genetically engineered ingredients in the product directly on the label.

B. Yes, it complies because it discloses that the product is "partially produced with genetic engineering."

C. No, it does not comply because the statement "partially produced with genetic engineering" is not one of the acceptable statements, and voluntary labels are allowed only when there is no detectable GM material.

D. No, the label is not in compliance with the required URL for disclosure about GM material.

[C is the correct answer.]

The labeling requirements are confusing to consumers, and clearly from this example, the labeling requirements were confusing to food producers, too. The bioengineering labeling rule is the opposite of the Midas touch — any bioengineered components make the entire product bioengineered.

So happy hunting in the pantry.

https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/898/246/1464271/

Effective Date: This rule becomes effective February 19, 2019. Implementation Date: January 1, 2020. Extended Implementation Date (for small food manufacturers): January 1, 2021. Voluntary Compliance Date: Ends on December 31, 2021. Mandatory Compliance Date: January 1, 2022. [83 Fed. Reg. 65814-65876, December 21, 2018].